The New Planning Manifesto illustrates the results and lessons learned from ‘The New Planning Dialogue’ carried out as a co-creative and collaborative series of dialogues for over two years from 2019 to 2020.

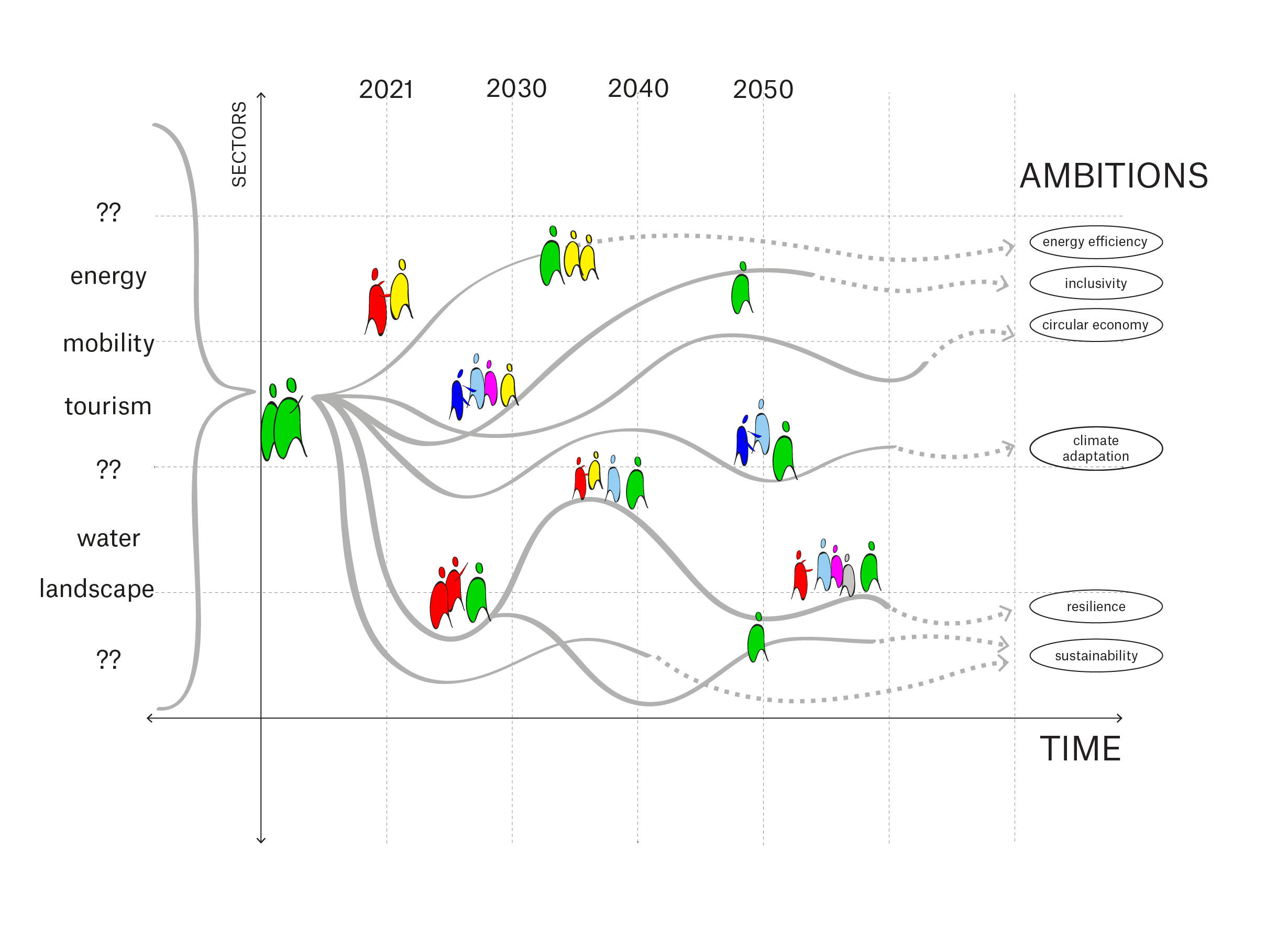

The global COVID-19 pandemic occurred simultaneously and largely shaped the dialogue, questioning how to react to and prepare for unexpected events in the planning process. From 2015 onwards several new agendas were presented, the Paris Agreement, New Urban Agenda, European Green Deal and the New European Bauhaus, acting as guidelines and initiatives towards a sustainable European future. The global agendas initiated the need for planners to come together and start a dialogue on how to realize these ambitions. Now with the emergency that IPCC report creates in the society and the kind off responsibility handed to our profession is evident for us to make edits in our conventional methods and be flexible as we move into transition. With this manifesto Manifesto

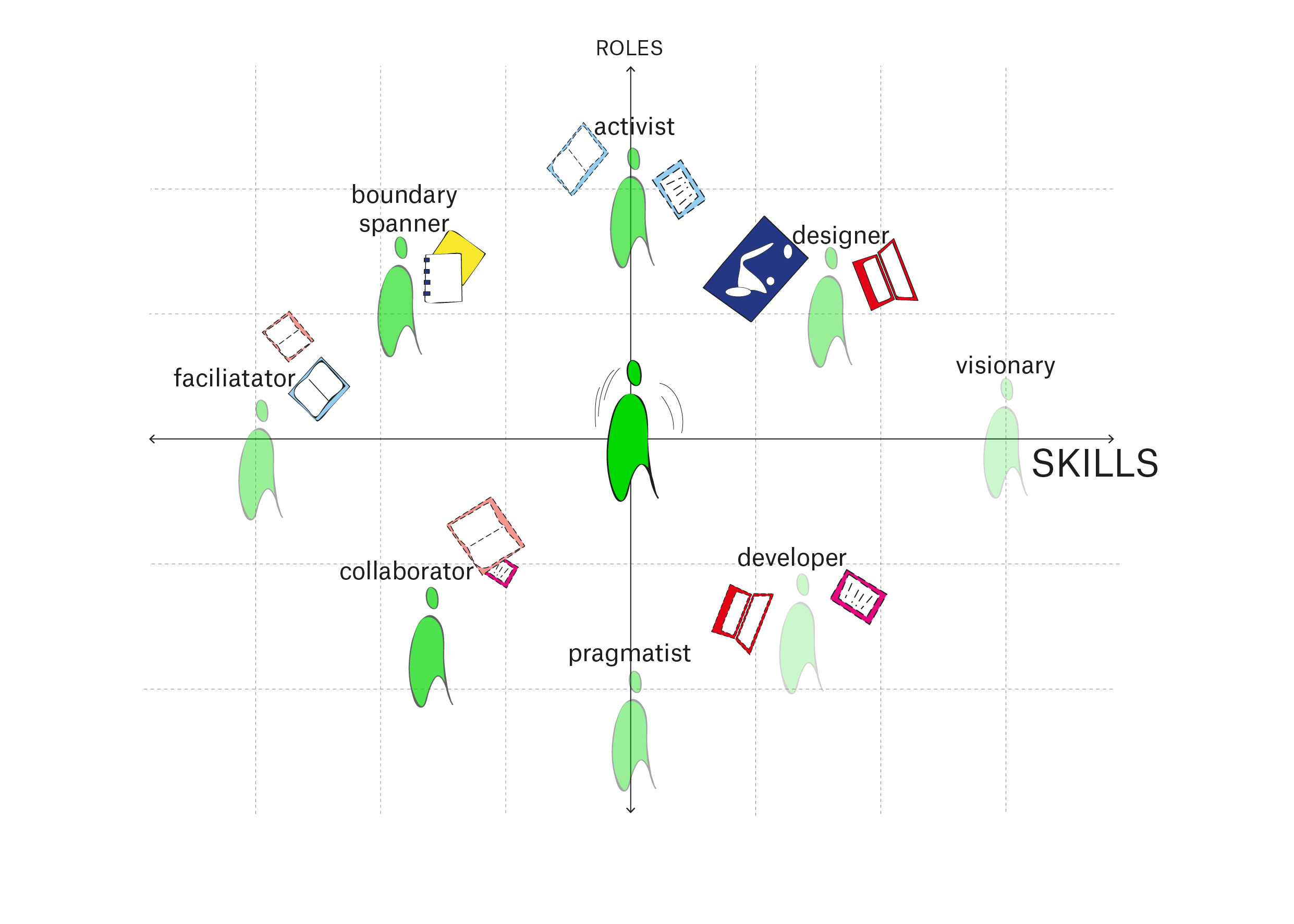

A document publicly declaring the position or program of its issuer. A manifesto advances a set of ideas, opinions, or views, but it can also lay out a plan of action (Britannica, 2022) , we encourage spatial planning to step up its role and responsibilities in tackling global challenges by showing variety of examples, good or bad. We actively encourage planning and design experts to bring a fundamental change in the practice of spatial planning. By forming new collaborations and working methods among planners and design experts, as well as, by working together with a wide variety of people from different fields.

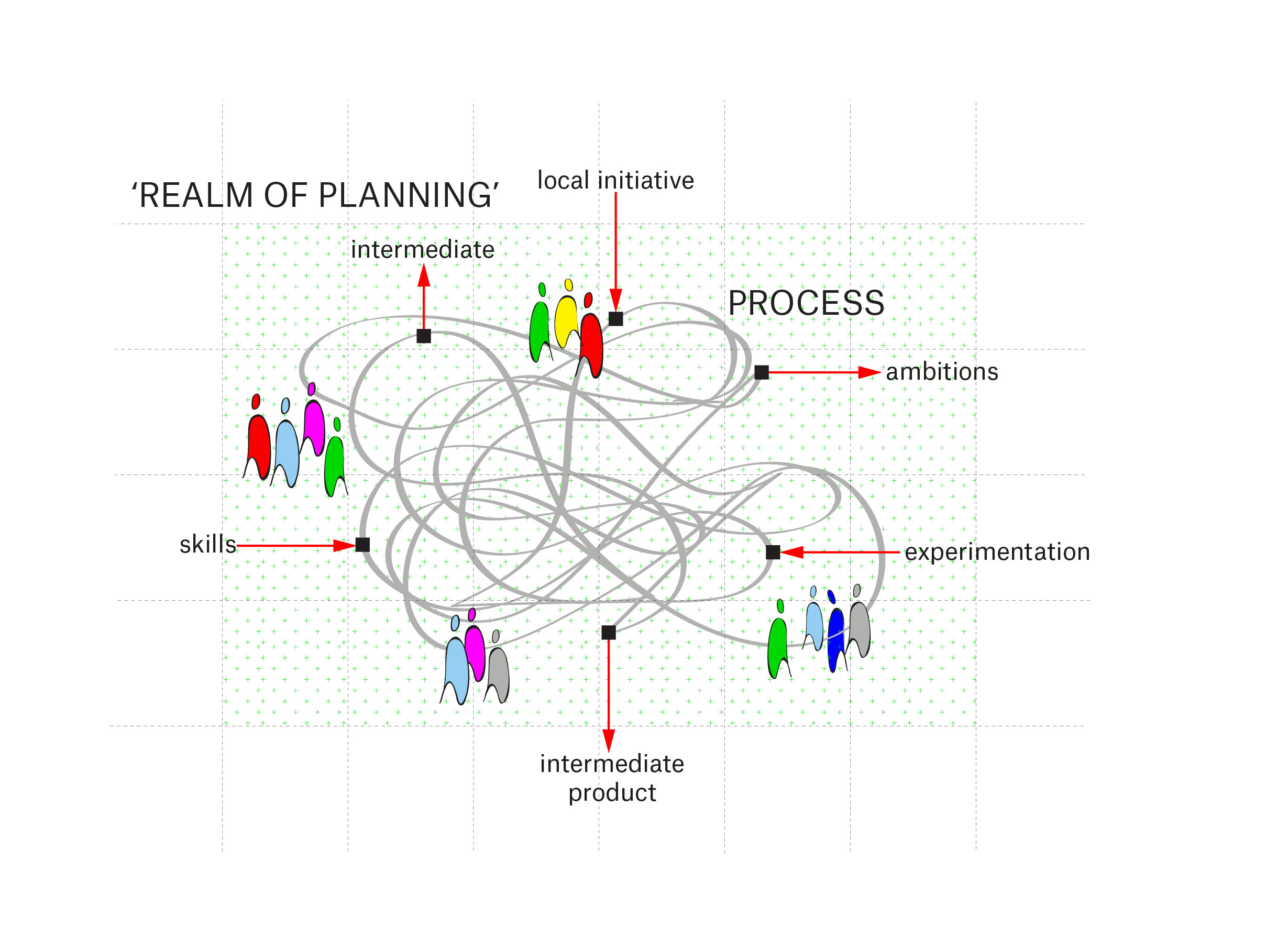

Bridging the gaps of research and practice ‘The New Planning Dialogue’, centred around the discourse on informal planning Informal planning

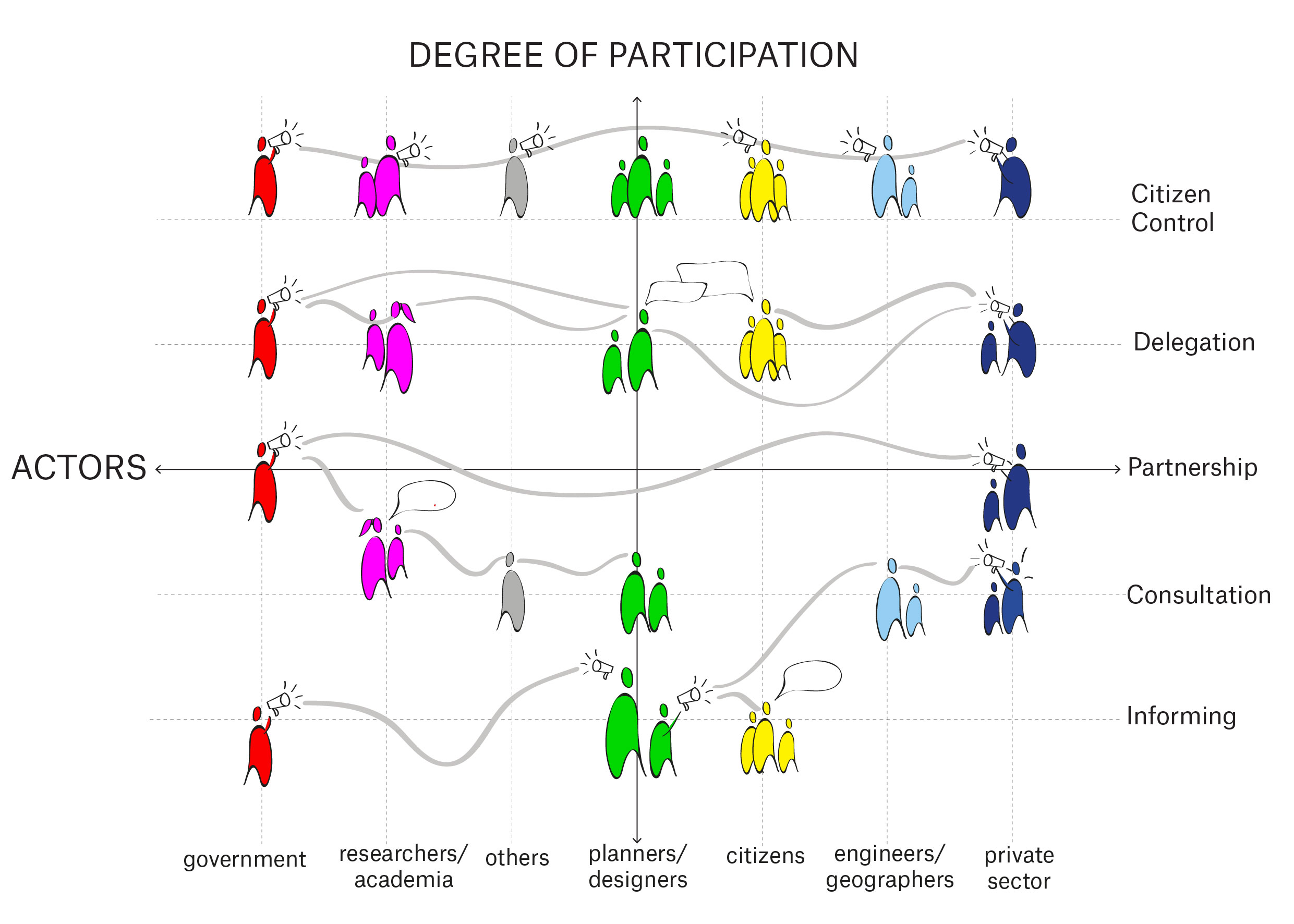

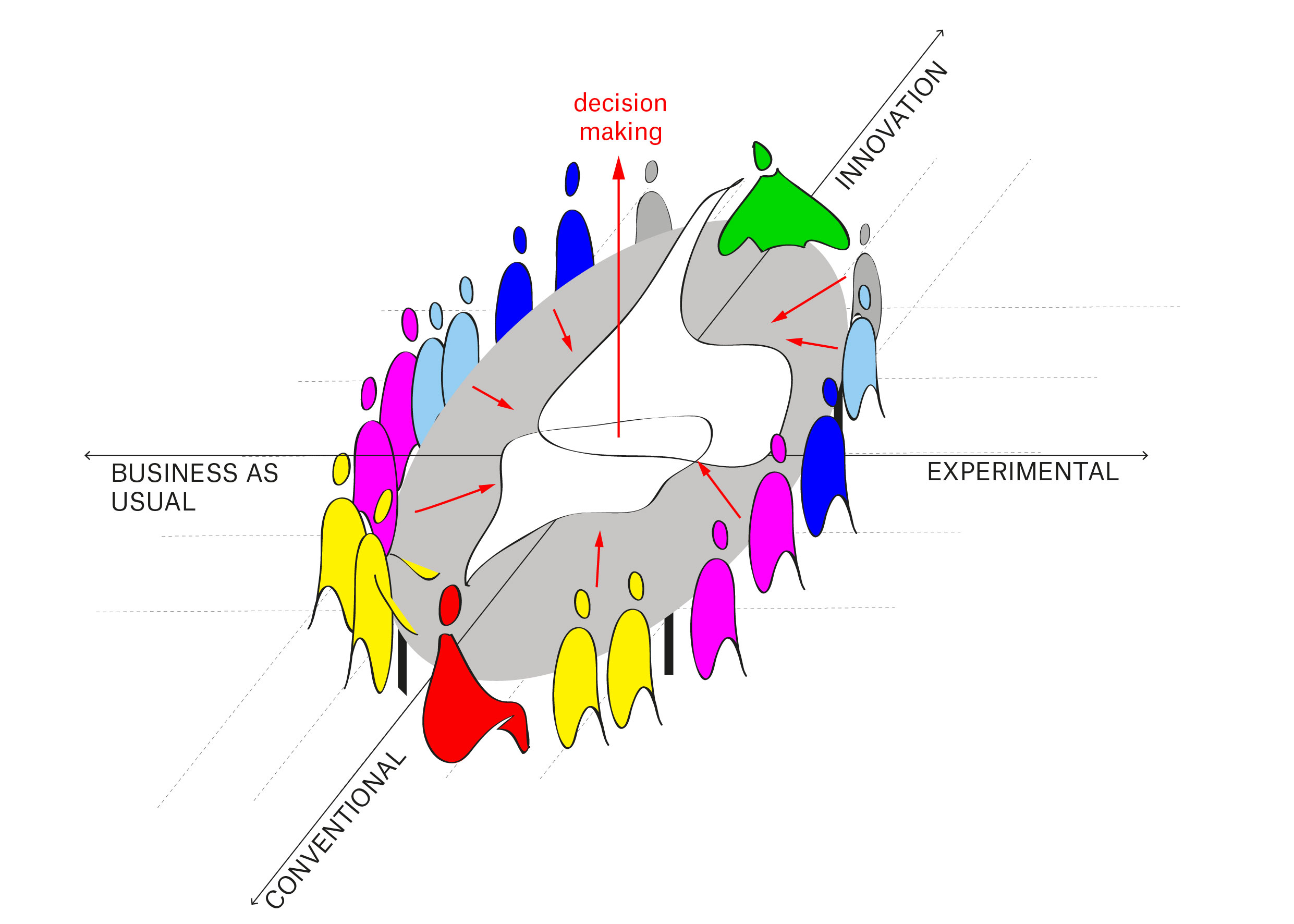

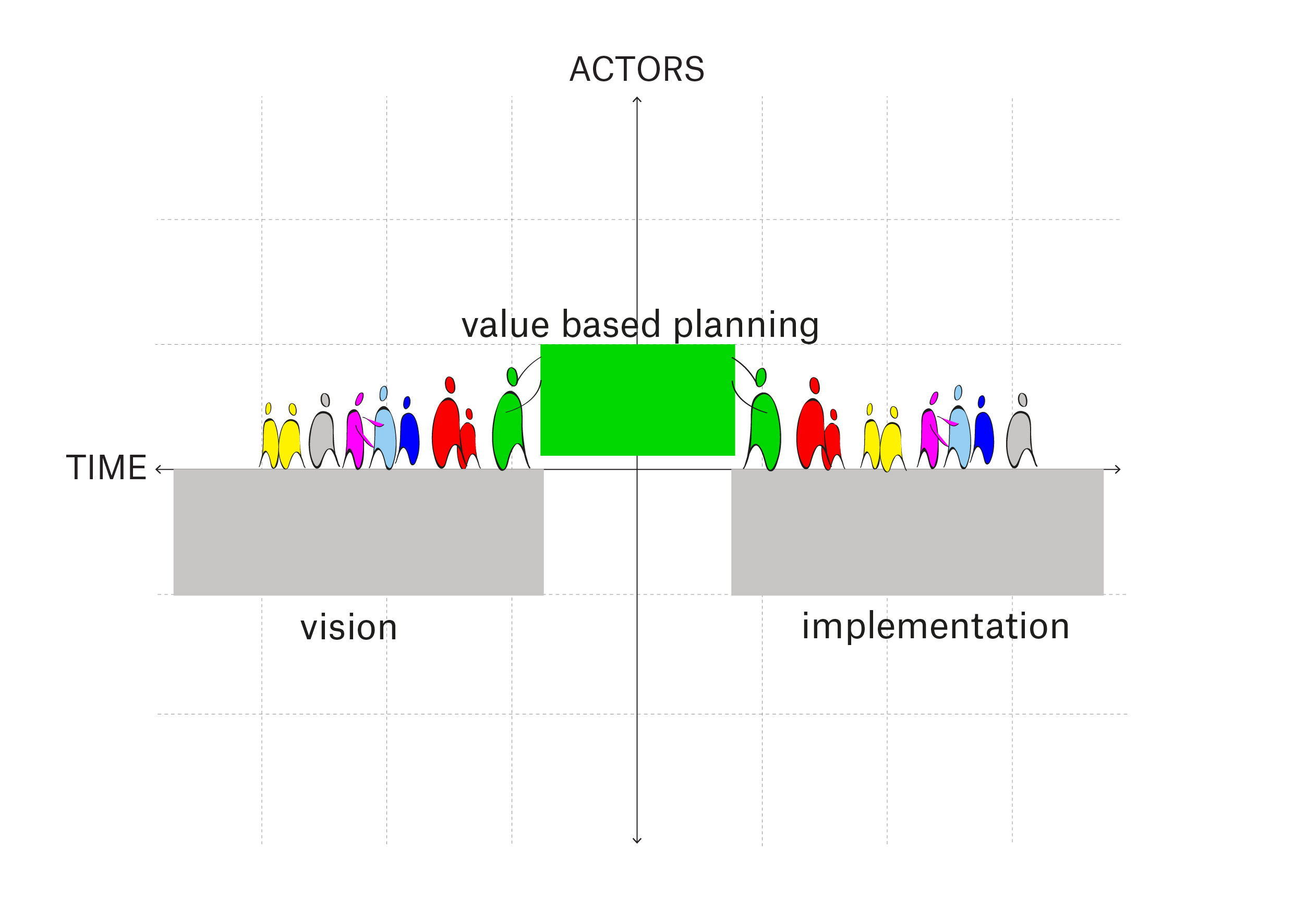

A non-binding supplement to official planning instruments that often increase public consensus, this includes the principles of collaborative dialogue, diverse networks, trustful relationships and tailor-made processes among interested parties (Theodora Papamichail & Ana Peric, ISOCARP 2019) methods challenged the status quo, towards a paradigm shift in the perception and practice of spatial planning from a product to a democratic and integrated process. The New planning is not just about using another (a new) toolkit or structure of planning, but rather itis about bringing change in the culture of planning and the planning community. This change in perception remains the most important element. It is essential to address the dilemmas in society and understand the mechanisms behind different complex environments, often containing interrelated aspects.

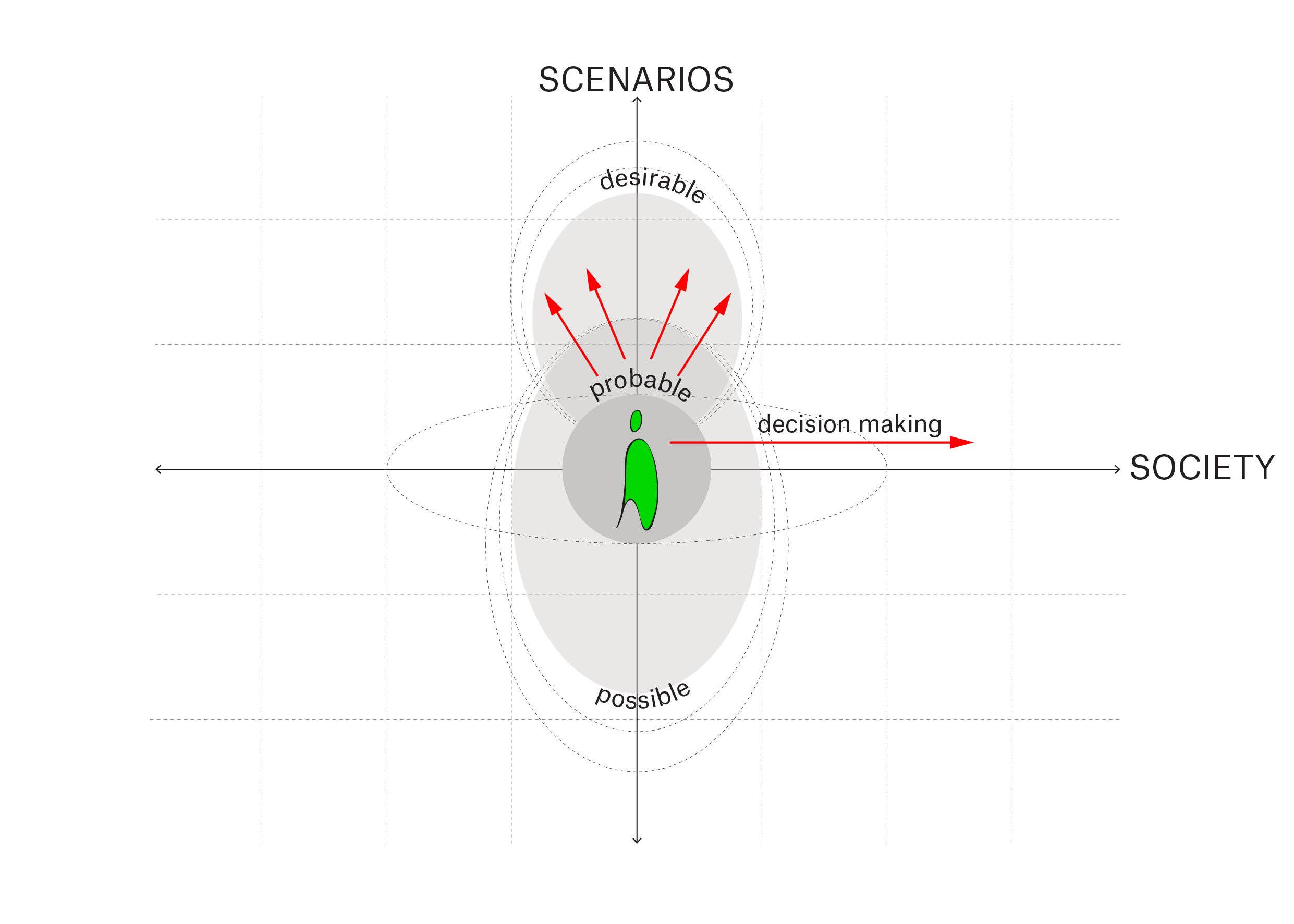

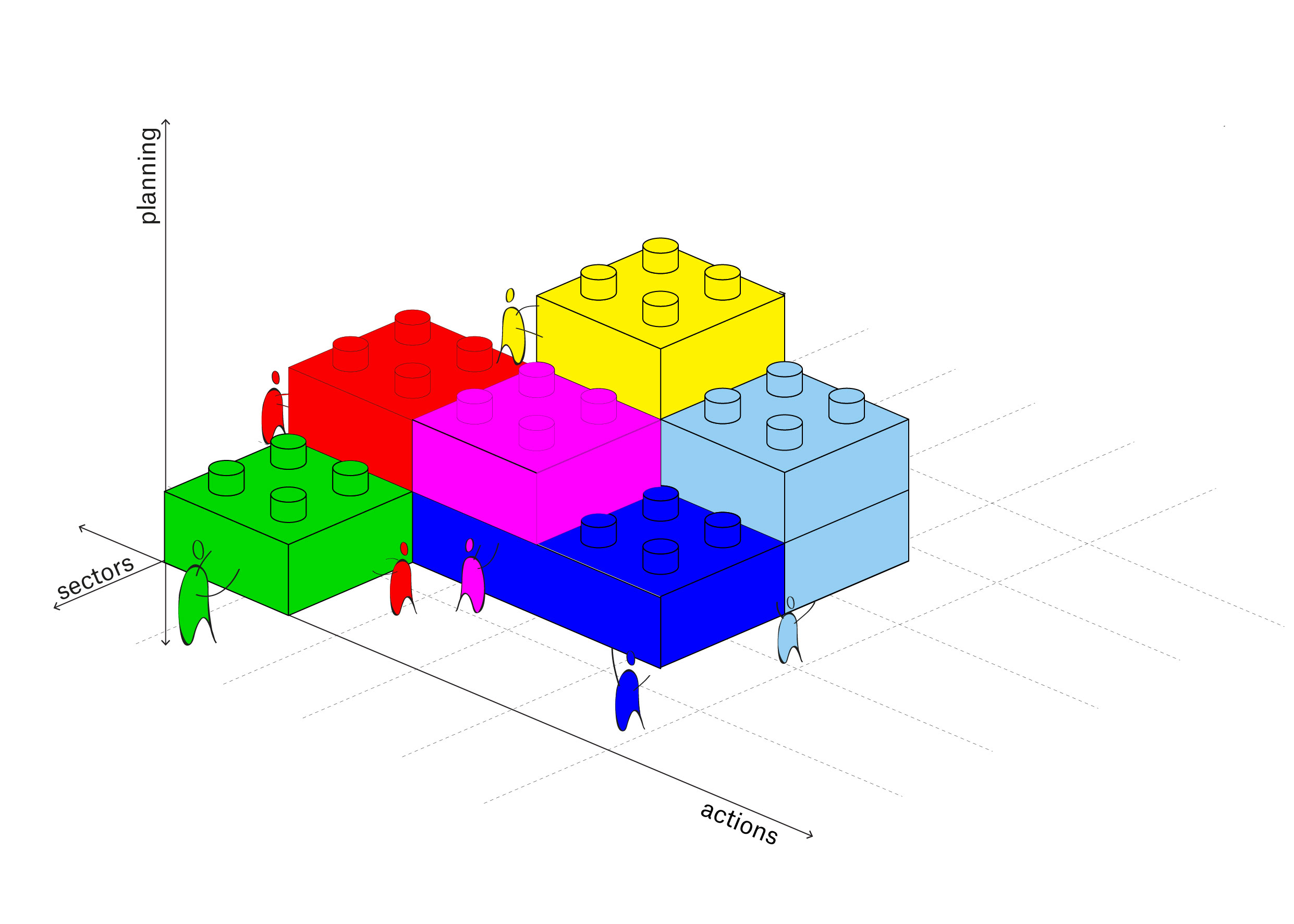

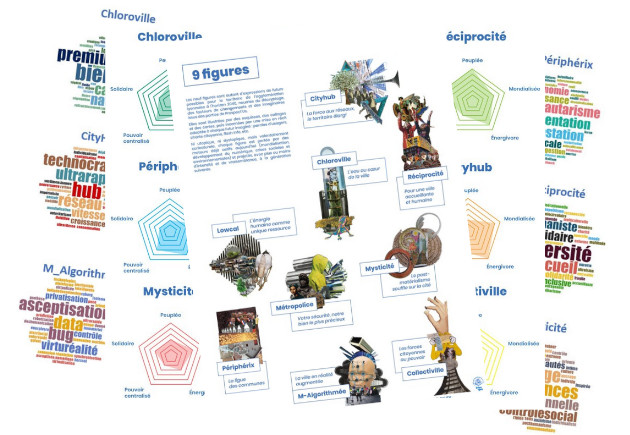

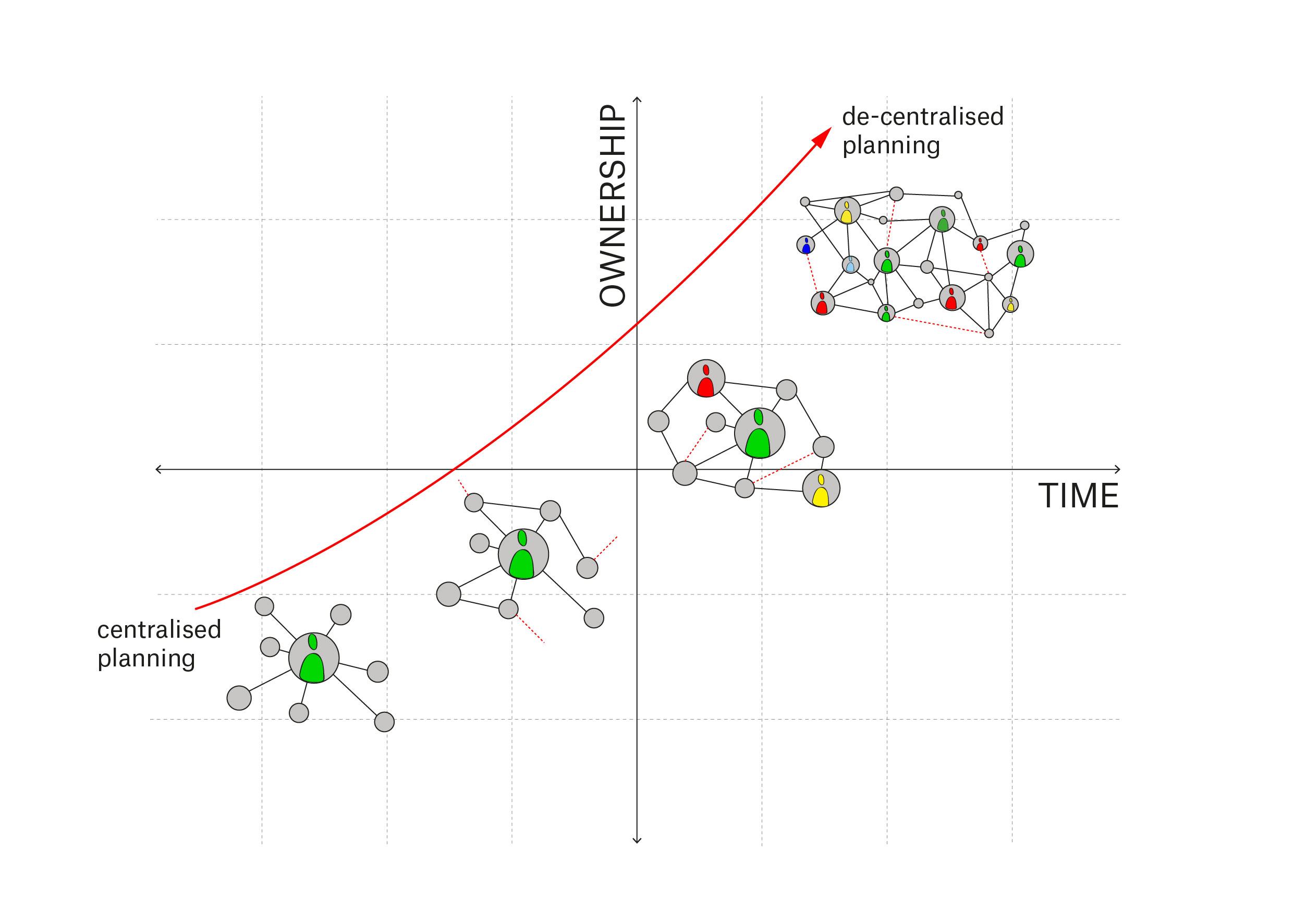

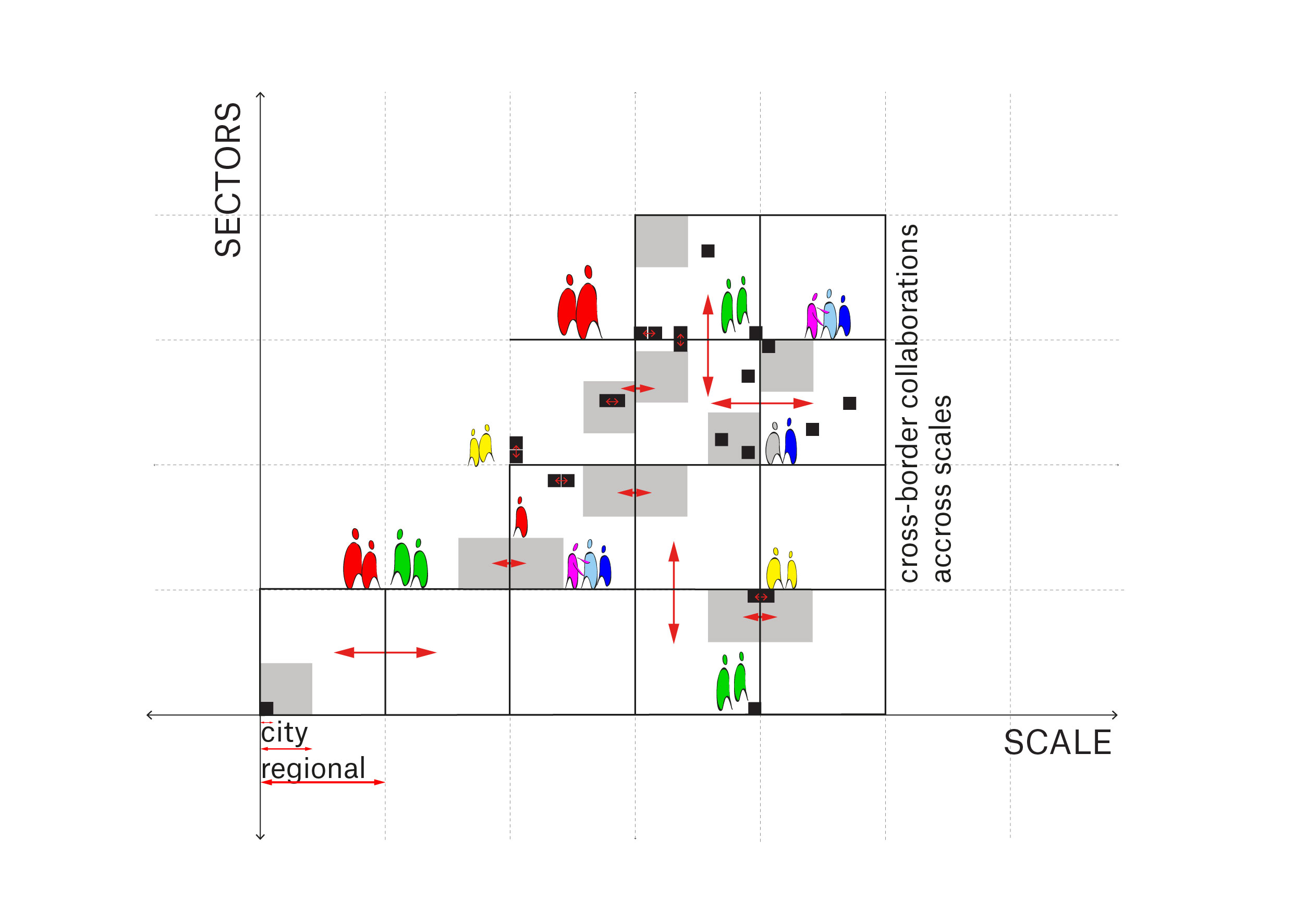

The New Planning as a method was the ‘new’ factor in the planning procedures in the Netherlands and in Europe. While enhancing on the new working ways of dialogue as a to get the relevant stakeholders on a table and as a research methodology, a lot of dilemmas were discussed and argued upon. In the momentum of searching for the ‘new’ in the New Planning, we sought out for innovative and inspirational solutions in variety of scale. Some arguments that questioned the current planning system were, the essence of digitalisation as an innovative driver towards societal development; planning as social contract between people, government, companies creating a way to deal with climate urgencies; searching for change in the normative goals and challenges; creating a new balance in democracy and ownership of space and cities; redefining “good life” for society amongst the global challenges; coping with scales of time, space and magnitude.

The manifesto as a method of achieving definition and a monumental and fundamental movement. This manifesto is for all the stakeholders of a sustainable society. It is a call for action for the planners and designers (but not limited) to come together and co-own the problems, co-create the solutions and collaborate. Hereby, Deltametropolis Association presents the following 10 points as a foundation for re-thinking planning as a profession, developed in collaboration with planning and design professionals for The New Planning Movement.